(Or: Why Historical Queerness is Complicated, Beautiful, and Occasionally Messy as Hell)

When I started writing queer characters, I didn’t expect to become a part-time amateur historian, therapist, and decoder of unspoken longing. But that’s what happens when you plop queer folks into past decades and tell them to live, love, and maybe solve a murder or two without getting arrested or excommunicated.

Right now, I’m waist-deep in a detective noir series set in 1930s Chicago—think fedoras, gin joints, and a paranormal investigator who’s a little too good at noticing things (especially when it comes to handsome suspects). And before that, I wrote a time-travel novel with scenes set in 1860. Yeah. That 1860. Civil War-era, “homosexuality is a criminal offense in every state” 1860.

I’ve learned a lot from these queer journeys through time. About shame. About resilience. About how love finds ways to survive—even when the world keeps trying to erase it.

The Unspoken is Deafening

If you’ve ever read a historical novel where two men are just very good friends and happen to share a bed because it’s “more efficient,” you’ve probably side-eyed your way into Queer History 101.

In the 1860s, I couldn’t write a character openly saying “I’m gay” without breaking the narrative like a poorly placed anachronism. So instead, there were loaded glances. Letters with double meanings. Physical closeness that a modern reader understands but the characters themselves might not even have words for.

And let me tell you, writing those subtle emotional gymnastics? Weirdly exhausting. But also really rewarding. Because it reminds you just how hard people had to fight to understand themselves—let alone find someone else who did.

Queerness Isn’t New (But It Was Dangerous)

I used to think of queer history as this slow unfolding—like LGBTQ+ people didn’t exist until we gradually “appeared” in the 20th century. LOL. Nope. We’ve always been here. What changed was the language and the risk.

In 1930s Chicago, things were just barely starting to crack open in the underground scenes. Speakeasies had back rooms. Men danced with men—quietly. Women lived together and were “confirmed bachelors” or “Boston marriages.” It was all hidden in plain sight, like a magic trick nobody acknowledged.

Writing queer characters during this time meant leaning into that tension. My detective might be quick with a pistol, but he’s slow to trust when it comes to romance. There’s always this edge of fear and secrecy humming beneath the surface—like the wrong word to the wrong person could end more than just a relationship.

It’s Not All Tragedy (Promise)

I worried, at first, that writing historical queer characters would mean constantly flirting with doom. And yes, there’s pain. You can’t sugarcoat laws, persecution, and violence.

But there’s also joy. So much joy.

There’s coded love letters and whispered confessions in moonlit alleys. There’s finding the one person who sees you when the rest of the world insists you’re invisible. There’s loyalty. Found family. Unlikely alliances.

In the 1930s detective story I’m writing, my main character finds moments of connection in places he never expected. A bartender who looks the other way. A former lover turned informant. A kiss stolen in the dark while jazz spills from a phonograph. It’s a little noir, a little gothic, and 100% emotionally fraught (my favorite flavor).

You Can’t Ignore the Era

Here’s a lesson I learned the hard way: you can’t just drop modern queer people into a historical setting and call it a day. You have to let the setting shape them. They wouldn’t have had access to the same conversations, communities, or even concepts that we do now.

In 1860, there was no “coming out” as we know it. There was no Pride parade, no TikTok explaining the difference between demiromantic and gray-ace. People figured things out in isolation—or not at all.

And while that’s tragic, it’s also a space for rich character exploration. The internal battles. The slow dawning of realization. The accidental discovery of joy.

There’s Always Someone Watching

This one hits hard, especially in the 1930s noir world. Even when you’re not being chased by mobsters or ghouls (because, yes, I threw in a supernatural twist), there’s always the social eye. The ever-present judgment. The “what will the neighbors think?”

That pressure shaped how queer people moved through the world. So in my writing, I try to show how small acts—like touching a hand for a beat too long—could be monumental. Intimacy is magnified under the weight of fear.

And yet, people still loved each other anyway. Because of course they did.

The Takeaway (If I Had to Pick Just One)

Writing queer characters across time has taught me this: we’ve always been here, quietly defiant, stubbornly tender, surviving by candlelight until someone could finally flip the switch.

As a writer, it’s both an honor and a responsibility to bring those stories to life—flawed, complicated, passionate, and human. Always human.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have a ghost-infested speakeasy to write and a very grumpy 1930s detective who needs to admit he’s in love with the man helping him solve a murder.

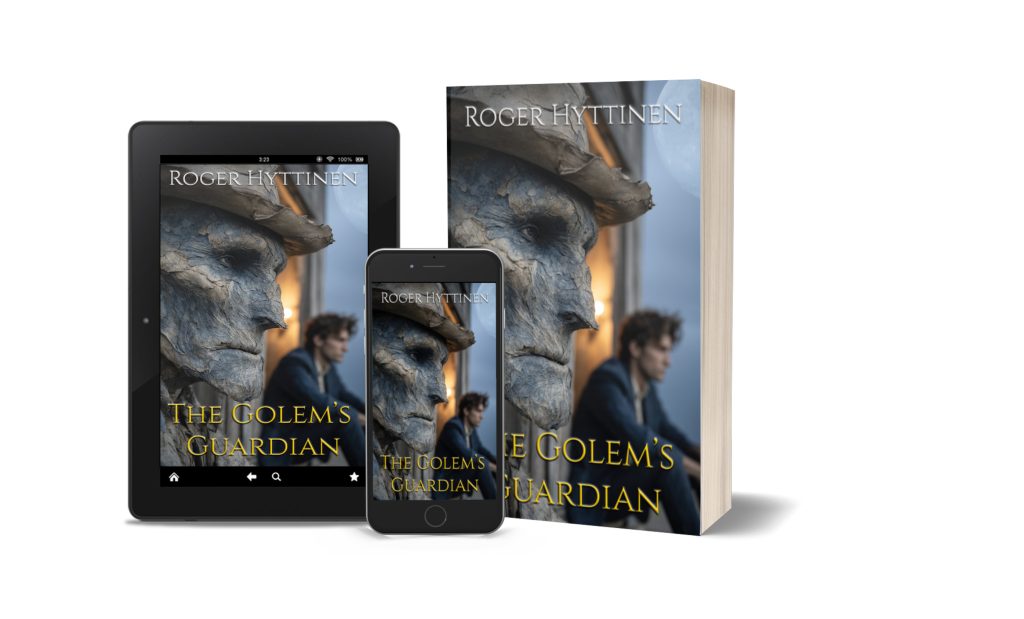

When Brooklyn librarian David Rosen accidentally brings a clay figure to life, he discovers an ancient family gift: the power to create golems. As he falls for charismatic social worker Jacob, a dark sorcerer threatens the city. With a rare celestial alignment approaching, David must master his abilities before the Shadow’s ritual unleashes chaos—even if using his power might kill him. The Golem’s Guardian